We need to

consider more carefully whether certain records are classics or not. Quella

Vecchia Locanda put out two LPs. Their eponymous effort of 1972 is very

often cited as a classic, and one does not wish to debate such opinions.

The second, Il Tempo Di Gioia, from 1974, receives negative comparisons

with the first, but is that fair or productive? Decidedly not, if the

second is a greater artistic achievement. There is some concern that the

second may be genuinely out of tune, whereas the first only falls under

mild suspicion. Yet the band makes a realistic effort to represent its

sometimes bizarre tunings as absolute pitch, and otherwise a high quality

of musicianship is pervasive. It may simply be that Il Tempo Di Gioia

requires more effort to appreciate. One will have to agree that its five

none-too-long tracks stack up well against the eight tracks of the first

LP, but I think that may be possible. Certainly they are all quite individual,

which cannot be said of the first. Then there is the strident quality

of this record, contrasting with the mellow atmosphere of the first. But

that’s the point, really, isn’t it. While the first LP seems

to know something about depth of good feeling, this one has a conception

of life as a whole, riddled with flaws, but strangely worth living.

We need to

consider more carefully whether certain records are classics or not. Quella

Vecchia Locanda put out two LPs. Their eponymous effort of 1972 is very

often cited as a classic, and one does not wish to debate such opinions.

The second, Il Tempo Di Gioia, from 1974, receives negative comparisons

with the first, but is that fair or productive? Decidedly not, if the

second is a greater artistic achievement. There is some concern that the

second may be genuinely out of tune, whereas the first only falls under

mild suspicion. Yet the band makes a realistic effort to represent its

sometimes bizarre tunings as absolute pitch, and otherwise a high quality

of musicianship is pervasive. It may simply be that Il Tempo Di Gioia

requires more effort to appreciate. One will have to agree that its five

none-too-long tracks stack up well against the eight tracks of the first

LP, but I think that may be possible. Certainly they are all quite individual,

which cannot be said of the first. Then there is the strident quality

of this record, contrasting with the mellow atmosphere of the first. But

that’s the point, really, isn’t it. While the first LP seems

to know something about depth of good feeling, this one has a conception

of life as a whole, riddled with flaws, but strangely worth living.

Alusa Fallax

chose for themselves a very strange name, and they were a pop group, no

less, before they essayed into the progressive. According to my information

their name dates at least back to the dawn of Itaprog. I can see how it

might relate somehow to the name of their sole album, Intorno alla

mia cattiva educazione, which came out in 1974 and surely cannot have

been recorded long before its release. But an accurate interpretation

of the Alusa Fallax name would maybe require an Indo-European grammar

and some comic books. Sorry to disappoint you, then, on the issue of what

the name means. There’s no way of telling here that Alusa Fallax

was ever a pop group, and not for a New York minute would one hesitate

to term their album a classic of the Itaprog. The cover – one could

also say that the cover is truly among the greats – perhaps the best

of all Ita covers – and that’s really saying something. The

music has one annoying drawback: it features a ritornello. Didn’t

that kind of thing go out of fashion five centuries ago with Monteverdi?

But it doesn’t fit too badly, for the music is entirely continuous

except for an artificial break signalling the end of the first and beginning

of the second side. Intorno alla mia cattiva educazione provides

evidence that high art can result from a negative appreciation of the

norms of education.

Alusa Fallax

chose for themselves a very strange name, and they were a pop group, no

less, before they essayed into the progressive. According to my information

their name dates at least back to the dawn of Itaprog. I can see how it

might relate somehow to the name of their sole album, Intorno alla

mia cattiva educazione, which came out in 1974 and surely cannot have

been recorded long before its release. But an accurate interpretation

of the Alusa Fallax name would maybe require an Indo-European grammar

and some comic books. Sorry to disappoint you, then, on the issue of what

the name means. There’s no way of telling here that Alusa Fallax

was ever a pop group, and not for a New York minute would one hesitate

to term their album a classic of the Itaprog. The cover – one could

also say that the cover is truly among the greats – perhaps the best

of all Ita covers – and that’s really saying something. The

music has one annoying drawback: it features a ritornello. Didn’t

that kind of thing go out of fashion five centuries ago with Monteverdi?

But it doesn’t fit too badly, for the music is entirely continuous

except for an artificial break signalling the end of the first and beginning

of the second side. Intorno alla mia cattiva educazione provides

evidence that high art can result from a negative appreciation of the

norms of education.

There is

no earthly reason to deny Museo Rosenbach classic status for their effort

of 1973 entitled Zarathustra. It is drawn from the purest fount

of the Italian progressive art. The music is lyrical, a fact that is far

too easily overlooked. Any possibility of levelling a charge of awkwardness

against transitional passages must be rejected on the grounds that transitions

lead generally once again into the mystical Zoroastrian realm that is

established at the outset. We are led to suspect that a genuine cult of

the Parsees is at play here somewhere, not just a rehash of the Zoroaster

of Nietzsche – but a resolution of this particular point hardly seems

necessary to our absorbing the musical experience. In any event, the chief

musical characteristic of this record is its exploitation of eastern tonalities

within an integrated progressive rock format. Throw in a heavy spiritual

undercurrent and you have something quite unique in the annals of Itaprog.

There is

no earthly reason to deny Museo Rosenbach classic status for their effort

of 1973 entitled Zarathustra. It is drawn from the purest fount

of the Italian progressive art. The music is lyrical, a fact that is far

too easily overlooked. Any possibility of levelling a charge of awkwardness

against transitional passages must be rejected on the grounds that transitions

lead generally once again into the mystical Zoroastrian realm that is

established at the outset. We are led to suspect that a genuine cult of

the Parsees is at play here somewhere, not just a rehash of the Zoroaster

of Nietzsche – but a resolution of this particular point hardly seems

necessary to our absorbing the musical experience. In any event, the chief

musical characteristic of this record is its exploitation of eastern tonalities

within an integrated progressive rock format. Throw in a heavy spiritual

undercurrent and you have something quite unique in the annals of Itaprog.

A secret

masterpiece came out in 1973: Vietato ai minori di 18 anni? It

was the third Jumbo LP and reflects both practical experience and artistic

maturity. Originally Jumbo played blues-rock as a vehicle for their distinctive

singer, Alvaro Fella, and his wistful yet cynical conception of amore.

Then on the follow-up DNA, from 1972, they amazed the listening

public with their new-found progressive sound. Some call that one a masterpiece,

but one can only maintain such a standpoint, I think, by observing how

unlikely it was for a lusty, rusty outfit like Jumbo to play progressive,

yet how convincingly they manage it on DNA. On Vietato,

therefore, they are seeking to press this progressive identity into service,

and there is no shortage of fine material here. For Jumbo could draw on

all kinds of riffs and segues from popular music backgrounds. Sounds already

almost familiar yet contrasting sharply with each other appear in synchronization

with an ever varying combination of instruments. Yet no particular instrument

has a limited identity – except perhaps the singer himself, though

he too works with different textures on a variety of levels to serve the

blending of contrasting sounds that principally characterize this record.

A secret

masterpiece came out in 1973: Vietato ai minori di 18 anni? It

was the third Jumbo LP and reflects both practical experience and artistic

maturity. Originally Jumbo played blues-rock as a vehicle for their distinctive

singer, Alvaro Fella, and his wistful yet cynical conception of amore.

Then on the follow-up DNA, from 1972, they amazed the listening

public with their new-found progressive sound. Some call that one a masterpiece,

but one can only maintain such a standpoint, I think, by observing how

unlikely it was for a lusty, rusty outfit like Jumbo to play progressive,

yet how convincingly they manage it on DNA. On Vietato,

therefore, they are seeking to press this progressive identity into service,

and there is no shortage of fine material here. For Jumbo could draw on

all kinds of riffs and segues from popular music backgrounds. Sounds already

almost familiar yet contrasting sharply with each other appear in synchronization

with an ever varying combination of instruments. Yet no particular instrument

has a limited identity – except perhaps the singer himself, though

he too works with different textures on a variety of levels to serve the

blending of contrasting sounds that principally characterize this record.

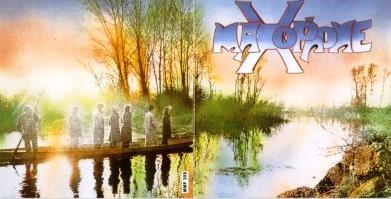

What’s

going on in this cover, that’s what I want to know. Is that Charon

punting the shades of the Maxophone across the River Styx? It sure looks

like it is. Does that mean there would never be any more Maxophone LPs

coming out after this eponymous one saw daylight in 1975? How could they

be so sure? What if one of the tracks had become an FM radio favorite

and somebody decided to put up money for another LP? What if one of the

band members assembled a new outfit and decided it would be appropriate

to use the Maxophone name? Nope, I guess we just have to accept that this

LP was deliberately intended to be the Maxophone’s first and last,

despite an interesting pop single the group put out some time after the

album. Actually, here you only see the six main guys in the group, but

several more (mostly girls) contributed to this album, and all kinds of

instruments can be heard. If there was ever such a thing as a progressive

rock orchestra, or even formal structures applying specifically to progressive

rock music, this is probably it right here.

What’s

going on in this cover, that’s what I want to know. Is that Charon

punting the shades of the Maxophone across the River Styx? It sure looks

like it is. Does that mean there would never be any more Maxophone LPs

coming out after this eponymous one saw daylight in 1975? How could they

be so sure? What if one of the tracks had become an FM radio favorite

and somebody decided to put up money for another LP? What if one of the

band members assembled a new outfit and decided it would be appropriate

to use the Maxophone name? Nope, I guess we just have to accept that this

LP was deliberately intended to be the Maxophone’s first and last,

despite an interesting pop single the group put out some time after the

album. Actually, here you only see the six main guys in the group, but

several more (mostly girls) contributed to this album, and all kinds of

instruments can be heard. If there was ever such a thing as a progressive

rock orchestra, or even formal structures applying specifically to progressive

rock music, this is probably it right here.